Chapter four - Confessions

We had called the palace in Zaruts several times "the tomb." Let us now, together with Mania and Antek, enter this "tomb" and observe it closely. The corridor, as previously mentioned, was dark and long; on both sides were doors leading to various rooms. Three rooms on each side: a library, a gymnasium, a dining room, two smaller rooms, and the Count's office.

Children of the Street

By: Janusz Korczak

Translation: courtesy of the Korczak educational institute of Israel

D. Confessions

We had called the palace in Zaruts several times "the tomb." Let us now, together with Mania and Antek, enter this "tomb" and observe it closely.

The corridor, as previously mentioned, was dark and long; on both sides were doors leading to various rooms. Three rooms on each side: a library, a gymnasium, a dining room, two smaller rooms, and the Count's office. The library was a spacious hall with large windows overlooking the garden. There were no cabinets in the hall, only shelves, and on the shelves stood more than five thousand volumes, all numbered. In the gymnasium, various apparatuses hung from the ceiling: ropes, rings, a trapeze, bars. On the walls were weapons of various types: swords, fencing masks, and rifles. There was nothing else there. In the center of the dining room stood a large oak table surrounded by chairs. Against the wall stood a large oak sideboard. On the walls hung portraits of the ancestors of the Zarutsy family. In the Count's office stood a large writing desk, and there was also a chair covered in oilcloth, a globe, maps, books, papers, and a large fireproof safe.

Antek and Mania were placed in the two small rooms, each in a separate one.

Mania was sleepy and tired. When she was left alone, she sat on a chair, rested her head in her hands, and sank into thought.

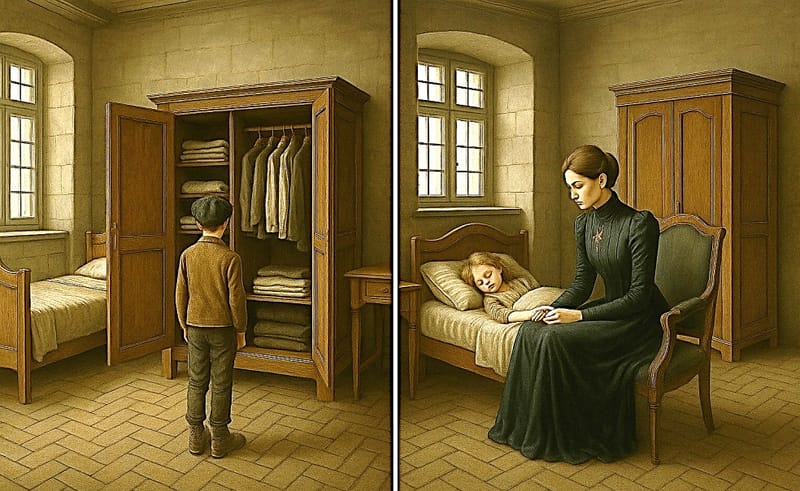

Antek, on the other hand, examined his room thoroughly.

"Oh! Oh! There's a bed, a wardrobe, a table, two chairs, and a sink. The window looks out to the garden. Not bad at all. But it’ll probably be deadly boring here," he thought to himself. "Well, we’ll see."

This whole adventure was starting to appeal to him. If his friends in Warsaw knew what had happened to him, they’d surely be astonished—they’d open their eyes wide in amazement!

There was a key stuck in the wardrobe door; Antek opened it. Half of the wardrobe was taken up by shelves on which underwear was neatly laid.

"Oh! Oh! Twelve clean shirts!" he whispered to himself—"that’s something. I wonder if they’ll let me take all of this with me."

The other half of the wardrobe was occupied by hanging clothes: a coat, trousers, a shirt.

"Not bad at all," Antek continued talking to himself, "but in the meantime, it would be nice to eat something."

At that moment, old Grzegorz entered and brought him a tray with a jug of milk, sugar, and bread.

"The master asked that you wash up before breakfast," the servant said and left.

"Well, if I have to wash, I’ll wash. What a joke. It could be a bit warmer here though."

Antek washed his hands and face (he almost never washed his neck and ears) and sat down to eat.

"Good milk, honestly. And what bread!"

He lay on the bed still dressed:

"Oh, hard bed. And I thought there’d be down bedding here, like at the Jewish innkeeper’s, or even better. Oh well."

He pulled out the last cigarette he had left from yesterday’s purchase and lit it.

"This is the life. If only it would always be like this. And it would be good to find a few friends nearby."

Antek fell asleep with the extinguished cigarette in his mouth.

Mania, too, fell asleep.

In one of the rooms on the floor above, the count, the countess, and the doctor had meanwhile gathered and were holding a consultation.

"These children come from some of the worst drunkard families," said the count. "They have absorbed the worst influences in their lives. They are very different from each other. We can bring the girl to the right path without much trouble, but we won’t manage the boy so easily. He is corrupt. It seems to me that he didn’t have such a terrible life at home, and he is stubborn and independent."

"What should we do now?" asked the doctor.

"I think," began the countess, "we should leave them alone for a while: give them a chance to reflect and think. Such a sudden change has surely made a strong impression on them."

"I agree," said the doctor. "But if we find that loneliness and idleness weigh too heavily on them..."

"In my opinion," said the count, "we must keep constant watch over them.[1]"

"That has already been decided."

"And we must be strict about it. So, who among us will keep watch?"

"I’ll go," said the doctor, and he moved to the next room, from where it was possible to see through two small holes in the floor everything happening in the rooms of Mania and Antek.

The countess went to pray in the chapel, the count went down to his office and wrote on the covers of two notebooks prepared in advance; on one he wrote 'Antek' and on the other – 'Mania'.

Then he took the first notebook and in small, neat handwriting wrote the story of his meeting with Antek and the account of his purchase, a story the reader is already familiar with from the first and second chapters of our story.

Let us peek into Mania’s room and observe the sleeping girl.

Her sleep was restless. She sighed heavily, and from time to time fragments of words escaped her lips. Her palm was pressed to her forehead, and her cheeks were flushed. Still, she did not wake up. Toward evening, a woman entered the room, lit the lamp that hung high from the ceiling, and woke the girl.

"Please undress and lie down to sleep."

"What?" asked Mania, opening her eyes in surprise. "Where am I?"

"Please don’t speak to me because I am deaf."

"But where am I?"

"I can’t hear. Please undress and lie down to sleep."

And she left.

The girl sat on the bed and tried to recall the events of the previous day.

"Ah, yes!"

She remembered everything that had happened.

But what did that woman say to her?

"Right, I have to undress."

She removed her rags, hung them on the bed’s railing, lay down, but couldn’t fall asleep.

The clock struck: it was nine o'clock. The lamp was dimmed by a greenish shade and its light barely dispersed the darkness. Manya was startled by the sound of the clock. She covered her head with the blanket.

She was alone here! There, in Warsaw, she had a drunken mother and now she had no one.

She felt hot. She pulled her head out from under the blanket and her gaze fell upon a cross hanging above the bed.

What is mother thinking? After all, she received money. Antek’s father must have deceived her. Nine o'clock... she must be at the tavern now. What is that deaf woman doing here? Where is Antek? What did they do to him? Why didn’t she see him here in the palace? Antek was smoking a cigarette and that gentleman looked at him with such a frightening gaze. Antek’s father – a drunkard.

Her thoughts became clouded and she slipped into a light doze, not quite asleep.

It seemed to her that two giant flowerpots filled with sand were suspended above her, and an invisible hand was shifting sand from one pot to the other. Each time, some of the sand poured over her, hot and heavy, ready to cover her completely.

From time to time, she tried to swallow a piece of wood that was in her mouth.

The clock struck: ten o'clock. Manya shuddered and awoke. Beads of sweat covered her forehead.

Was she asleep or not?

No. She was not asleep. Even now she wasn’t asleep, and yet she could see everything so clearly and hear the ticking of the clock.

Suddenly she heard a soft whisper and understood the words that floated down to her from above:

"Go to her!"

Manya trembled. Who was speaking? To whom? To her, to Manya. But to whom was she supposed to go?

And the child, daughter of a drunken mother, who had suffered abuse at the hands of a criminal mother in decline, groaned with pain and helplessness:

"Mama!"

She was startled by the sound of her own voice, a sound that was foreign to her, and as if compelled by some higher force, she cried out again:

"Mama, mama, mama!"

Tears burst from her eyes and streamed down her cheeks.

At that moment, the door opened quietly. Standing in the doorway was the countess, dressed in a black dress that clung tightly to her figure. Her calm gaze met Mania's agitated eyes. The woman bore a strange resemblance to the gentleman who had brought them to the palace.

"Maybe he turned into a woman?" flashed through her feverish mind.

The Countess approached the child's bed, knelt beside her, slid one hand under the pillow, and with her other arm embraced the little girl.

Mania's breath caught in her chest.

"Mania, why aren't you asleep?" the woman whispered softly.

"Because I'm scared, terribly scared."

"What are you afraid of, Mania?"

A touch of sorrow could be heard in the woman's voice, accompanied by great compassion and warmth.

"No, Mania, there's no need to be afraid. You are among good people, my child. Relax and sleep."

"I can't."

The countess kissed the child's feverish forehead.

"My poor, dear child."

Manya shuddered.

"Why are you kissing me, ma'am?"

"Because I love you."

"Why do you love me?"

"Because you are suffering, my child."

"And how do you know that, ma'am?"

"I can feel it, my little one."

These three questions Manya asked almost in a single breath, one after the other.

"Who are you, ma'am?" Manya asked again.

"I am the one who wishes to take the place of your mother."

"But I have a mother."

"But your mother is an unfortunate woman."

After a long moment of silence, Manya said in a firm, loud voice:

"My mother isn't unfortunate, she's vile, and I hate her. I would... I would... I would kill her. She..."

"Don't speak now, my child. Try to fall asleep. We'll talk more about these things later. Sleep now."

"But will you stay here, ma'am?"

"I will."

"All night?"

"All night."

"Can you lie here next to me, ma'am?"

"No, Manya, I'm fine like this."

"But please don't leave, because I'm scared."

"I will stay right here beside you."

Manya closed her eyes and tried to sleep. But the thought of being alone again wouldn't let her rest.

After a long while, she opened her eyes and her gaze met once more the gaze of her new guardian. The woman's lips were moving in a quiet whisper.

What are you saying?”

“I’m praying.”

“For what?”

“I’m praying for your happiness.”

“Not for your own?”

“No.”

“I prayed today too, but I asked for happiness for myself. I asked Jesus, our Lord, to make that gentleman who took me give me a lot of money to throw in my mother’s face, maybe a hundred or a thousand rubles, and to beat her properly until the blood runs. Yes, for money she’ll agree to be beaten.”

“Your prayer, Manya, our Lord Jesus will not accept.”

“Why not?”

“Because it was a bad prayer.”

“There are bad and good prayers?”

“Yes.”

“And why was mine a bad one?”

“Think for yourself.”

“Probably because I wanted to hit my mother.”

“Yes, my child.”

“But ma’am, you simply don’t know my mother!”

Manya rested her head in her hands, propped herself up on the pillow, and began to speak:

“You don’t know, ma’am, that my mother killed my father. I never knew him because he died when I was three. I don’t remember him at all. But she told me herself. She used to say to me: ‘You snake, you vile soul. I’ll finish you off with beatings just like I did to your father.’ And do you know why she used to beat me, ma’am? Because after my father died, my mother married someone else, and he was just like her. They beat each other and both of them beat me. All the time. Then he disappeared. But it got worse, because my mother had another husband, and then another one after him. I was only seven then, and I had to serve them. My mother wanted me to call each one of them ‘Father’ and I didn’t want to. So she beat me and starved me, and even threw me out so I’d go and beg for alms. When my father was dying in the hospital, he kept asking for just one thing: that I wouldn’t be left with her. But who could I go to? When I got a bit older, she started being afraid of me. When she came home drunk and couldn’t even move, I would beat her.”

"I’m not even sure she knew what was going on. But what could I really do to her? I was afraid to scratch her, because she might guess it was me who gave her the scratches, and she thought the bruises were from falling. And even so, she would still beat me afterward. You know, ma’am, I wanted to hang myself. I had already placed the stool, but it was too short, so I went to look for Antek to help me move the table. He guessed what I was up to, because he helped me as if everything was normal, and left. But he stood by the door and peeked through the keyhole. He told me afterward. I placed the stool on the table, tied the rope, and had already put my head through it, but he burst in and shouted: 'Manya, what are you doing?' I got scared and fell to the floor. Then Antek went to his father and told him. That gentleman bought us from Antek’s father. Antek’s father went to my mother and told her: 'If you touch her one more time, I’ll bring you to the police.' My mother argued with him, but she was frightened, because she had probably already been jailed a hundred times. Oh, how happy I was then! I heard that for all the beatings she gave me, she could’ve gone to real prison with handcuffs on her hands and feet. After that, she begged me not to say anything, because the neighbors got involved too. In our building lived a carpenter, a kind and decent man, like my father. That carpenter said he would come and testify. His wife tried to convince him to drop the whole matter and said to him: 'Why bother going to court? The girl’s just like her mother.' Because she was angry at me."

"After that, Antek’s father started paying my mother two zlotys a day for me, and I paid him back from what I earned. I had to earn half a ruble, because he wanted to make forty groszy a day profit off me. He argued with my mother all the time, because she knew I was bringing in more money. But he threatened her with jail, so she took it out on me. Later she started to be afraid of me too, because I used to tell her I’d take her to court. And Antek’s father—he only pulled my ears, or punched me, or twisted my arm. But he didn’t slap me so there wouldn’t be bruises. Because if I looked prettier, I could get more money for the flowers I sold."

"Sometimes I gave him all the money I earned, and sometimes I made a little more and bought myself some cookies, chocolate, or candy. But when I made less, Antek would always give me extra, because he loves me—and I love him too. Even though now he’s not quite like he used to be. He even told me himself: 'Because of you, people laugh at me; you won’t even let me kiss you, like you’re some kind of countess or something.' But I always thought to myself, it doesn’t matter—because if he ever leaves me, I’ll just hang myself, that’s all."

Mania finished her words. Her eyes burned like two coals. Blood seemed about to burst from her flushed cheeks; through the holes in her torn gown, one could see her childish chest rising and falling intensely. She was a girl-woman who, because of her wretched life, had matured too early and stood on the brink of losing her world to decay.

No. Mania had found a solution to the life of misery that had been destined for her—a life that led from the police station to the hospital to prison, to crime: she had planned to take her own life.

Mania is the first street child, among a long line of children like her, that I will present to you.

Mania was deeply moved by her own story. She looked into the green light cast by the lamp as though she saw there all she had told the countess—and also things she hadn’t told, either because she forgot, or because she was too ashamed to say them.

Had Mania looked, instead of at the light of the lamp, at the face of her listener, she would undoubtedly have been appalled. For she would have seen in her face an expression of contempt—but also a feeling of boundless love, of awe, of endless compassion, of terrible pain, and finally, an expression of utter exhaustion, born of an intense inner struggle.

While Mania told her story, the countess did not utter a single word, even though her soul longed to cry out. When Mania fell silent, the countess opened her mouth several times to say something, but no words escaped her choked throat.

At last, the countess embraced the child warmly, tried to kiss her, but at that very moment lost her balance and collapsed unconscious onto the floor.

Mania hadn’t even managed to cry out when a stranger entered the room, took a pitcher of water, and poured a little over the fainted countess’s face. She opened her eyes.

"Strength, courage, madam!" said the man, who was the count’s doctor and friend.

"It’s all right now. You may go," she said.

The man left.

Mania was unable to understand anything that had just happened around her. But she grasped one thing: she was surrounded by spirits—kind spirits.

"What happened to you, madam?" Mania asked.

"Nothing, my child. I’m just very tired."

"Because you knelt for such a long time. Lie beside me. Maybe I repel you? Maybe you don’t love me anymore?"

"I love you, my child. I love you even more."

The countess sat down on a chair, rested her head on Mania’s pillow, and said:

"Sleep, Mania."

And the girl fell asleep while holding the woman’s hand.

The next day, the countess sat in her office, leaning over a notebook bearing the name “Mania.” She was writing a summary of her conversation with the girl. Three times, she stopped writing and put down her pen due to the trembling in her hand. She ended her report with the following note:

“I believe my brother is mistaken. Nothing can be done with these children. They carry the seeds of corruption in their blood. They have absorbed so much evil in their early years that nothing can heal them.”

Beneath the note written by the countess, the count added his own remark:

“I believe that great love and a willingness to invest unlimited work in them are enough to rehabilitate the children.”

Late that day, Mania opened her eyes, slowly looked around her room, and recalled the recent events. She remembered her nighttime confession to the strange woman—and suddenly felt a wave of anger.

“Why did I tell her everything?” she thought. “What does she care what kind of mother I have? I don’t want her to come to me, to talk to me, to speak with me. I don’t need a caretaker. I don’t need anything at all. Antek is right: we have to escape. I have to see him and get ready. I want to go back. Now we’re free. I don’t have to go visit my mother. If they sold us, and if we get all the papers, what can they even do to us?”

The countess entered the room, approached Mania, and asked her with an artificial smile on her pale face:

“Did you sleep well?”

“Yes,” the girl said, her eyes lowered.

“Are you angry with me?”

“What would I have to be angry with you about?”

“I know, Mania, that you're angry with me. I myself asked you not to tell me your life story until you got to know me well, until you were convinced that I only wished you well. Didn’t I ask you that?”

“Yes,” Mania mumbled, “I want to see Antek.”

“Antek is still asleep. He’ll come to you soon. Get dressed, Mania. Do you want me to leave?”

“It doesn’t matter to me.”

“No, Mania, speak to me honestly. Do you want to be alone?”

“Yes.”

“Then I’ll go. Remember, Mania, we can only love one another if we always say what we think and feel. I already love you, my child, and I hope you’ll grow fond of me too. Right now, don’t you like me at all?”

Mania was silent.

“Tell me, Mania, quietly, in my ear.”

“No,” Mania whispered, “but maybe I’ll like you later. Right now, I can’t like anyone… except for Antek,” she added after a moment.

[1] Systematic observation of the child's behavior was one of the most important methods of experimental psychology and pedagogy, and later of pedology (the science dealing with the study of the child's life and mental and physical development). The pioneers of this method in the West were Wilhelm Preyer and Stanley Hall, in Russia – Konstanty Uszynski, in Poland – Jan Wladyslaw Dawid (1859-1914), the author of a detailed questionnaire for monitoring and observing children (1887). Korczak kept a regular record of the behavior of his charges in "The Orphan Home" and set up tables and diagrams describing their development. An early testimony of his interest in the monitoring method can be found in "The Confession of a Butterfly," a story undoubtedly based on Korczak's teenage diary. In a passage dated January 18 (1893), he writes: "I intend to write a large study on 'Childhood' and for it I will diligently collect material from myself and my friends. I have compiled a questionnaire (...)"